An act of no choice: the “integration” of Timor-Leste, 1976

E-dossier #6. An act of no choice – Sporting Club, Dili, 31 May 1976

On 31 May 1976, the Sporting Club in Dili hosted a controversial ceremony in which a handful of Timorese legislators selected by the Indonesian-imposed “Provisional Government of East Timor” petitioned unanimously for annexation by Indonesia. On 31 July, Indonesian president Suharto accepted the petition and declared Timor-Leste to be Indonesia’s 27th province, under the name “Timor Timur” (East Timor).

United Nations and Commonwealth documents from this time period illustrate the illegality of the assembly calling for annexation, its pre-determined outcome, and the different stances taken by the UN and some Western powers.

We can conclude:

- The assembly was designed to make a major international problem, the invasion of Timor-Leste, disappear

- It was modelled on the illegimate “Act of Free Choice” held in West Papua in 1969, less than seven years earlier

- Indonesian officials consistently refused to take part in peace talks during this period, preferring to work through the “Provisional Government,” and used the 31 May assembly as a justification for not participating in talks

- Australian politicians set the path for other Western governments debating whether to attend

- The United Nations always viewed the assembly as illegitimate and never considered attending

- The Assembly’s outcome was decided in advance, and this was known at the time

The story can be told from a series of primary source documents produced in 1976. This briefing book relies primarily on United Nations archival documents, but also draws on documents from Australia, New Zealand and Canada. File number references are available on request. These documents should be read in conjunction with published histories of Timor-Leste’s international history.

All documents available in this folder.

Document 1 is a map of areas of control in Timor-Leste at the end of February 1976, almost three months after the invasion by Indonesian “volunteers.” Prepared at the UN, it showed that Indonesia controlled three of the four largest population centres including Dili and Baucau, but that Fretilin’s Democratic Republic of East Timor (DRET) controlled the majority of the territory.

All parties paid lip service to the principle that the war in Timor-Leste should be ended and the people be granted their right to self-determination. Eventually, the 31 May assembly was Indonesia’s answer to how to allow the expression of self-determination. Even before that assembly was proposed, the DRET pointed out in Document 2: “To speak of ‘an act of self-determination’ before the Indonesians withdraw is blatant hypocrisy” which would violate international law and “connive in the legitimation of genocide.” In an appeal to the UN Security Council, it called the resistance and reconstruction work of “a whole nation” that was then going on “the most genuine and unquestionably courageous act of self-determination.”

Early in 1976, the UN Secretary-General, Kurt Waldheim, consulted representatives of Indonesia, Portugal and the DRET. The record of conversations with each of them make up Document 3. Portugal ambassador J.M. Galvao Teles stressed that “everything should be done to ensure self-determination” and sought negotiations. Indonesian diplomats made it clear that they were not willing to negotiate. Ambassador Anwar Sani told Waldheim Indonesia “could not visualize” full negotiations and “was not prepared to participate.” He urged instead that the DRET talk with the Indonesian-backed “Provisional Government” (PGET) in Dili. DRET foreign minister Jose Ramos Horta said his government would negotiate with Indonesia but not the PGET, which was “only an Indonesian puppet.” He reported an Indonesian plan to hold a “popular assembly” of some 500 people to perform an act of self-determination, the first time this appears in the UN Secretariat, and said Fretilin would reject it and “continue to fight.”

In April, the PGET legislated the popular consultation through an executive act (Document 4), mandating self-determination through “consensus and consent,” a reference to the Javanese concept of musyawarah (consensus through deliberation). The act claimed that this method was “in accordance with the traditions and identity of the people of East Timor,” ignoring the fact of full elections held before the invasion. The structure of consultation was clearly modelled on the 1969 “act of free choice” in West Papua, with a “Deliberative Council” made up of two representatives from each of the 13 districts (conselho). The PGET’s parliament would be added to these members to create a larger voting body, that would express its opinion on self-determination on behalf of the nation.

“Whole procedure is reminiscent of that arranged for act of free choice in W Irian [West Papua,” noted the Canadian embassy in Jakarta, briefed on the plans for an assembly in Dili (Document 5). Given this, Western governments would need to carefully consider whether it was proper to attend.

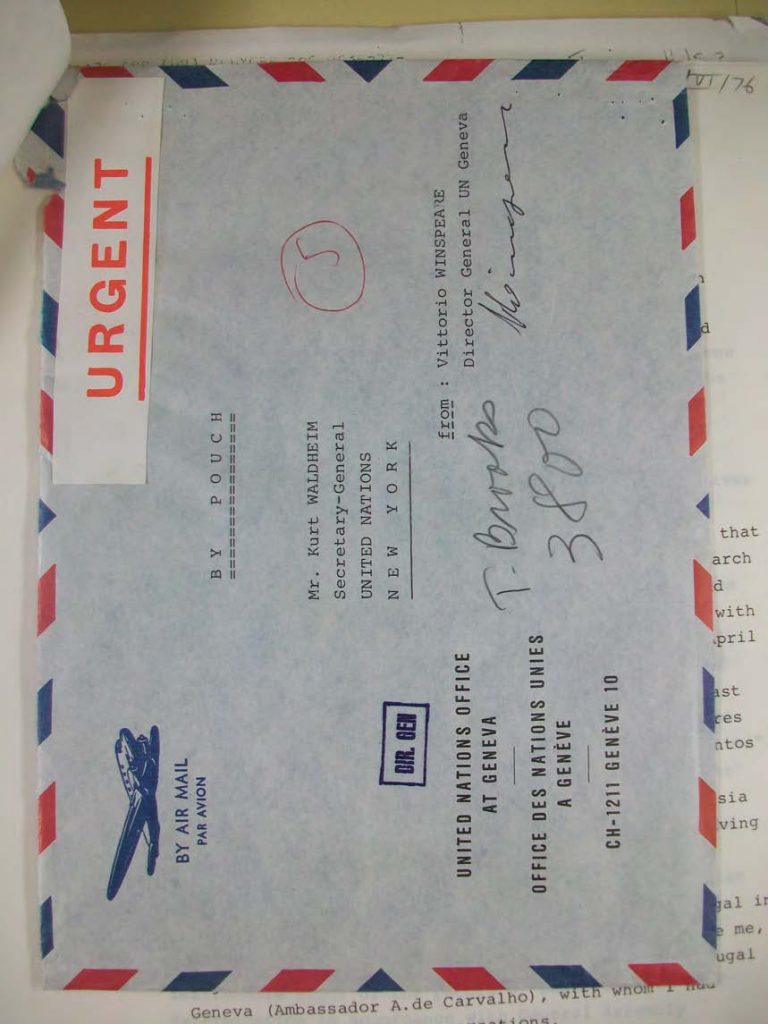

Pressed by Portugal, UN special envoy Vittorio Winspeare Guiccardi said “neither the United Nations nor the Secretary-General could subscribe to unilateral action on the part of Indonesia,” according to Document 6, the record of his meeting with Ambassador Galva Teles. The UN never retreated from this stance, but Winspeare was willing to entertain the idea of a beefed-up assembly to decide on self-determination.

As preparations for the assembly continued, Indonesian foreign minister Adam Malik categorically denied that Indonesia would annex Timor-Leste before August. His words were conveyed by the Indonesian UN mission in Document 7.

The UN remained unwilling to lend its hand to any Act of Free Choice-style method. While references to Winspeare being willing to accept an assembly appear in Australian documents, the Special Committee of 24 dealing with decolonization issues (and thus with Timor-Leste) was adamant that “any United Nations presence at this stage would only serve to rubber stamp the annexation process, and therefore should be avoided,” in the words of Document 8, a memorandum from Under-Secretary for Political Affairs and Decolonization Tang Ming-chao to Secretary-General Waldheim.

With the assembly scheduled for 31 May, PGET representatives Mario Carrascalao and Tito dos Santos Baptista tried to get a UN observer presence, arriving in New York to lobby for this on 24 May. The assembly was now to consist of 27 people – two from each district, with an extra representative for one district, plus five representatives from political parties and five traditional chiefs and religious authorities. They met the acting chairman of the C24, Tom Vraalsen of Norway (Document 9). Vraalsen stressed that the meeting was unofficial and the UN in no way recognized the PGET as a government, but agreed to inform the C24. In a meeting the next day, C24 chair Salim Ahmed Salim of Tanzania also provided no encouragement.

The C24 formally announced its refusal to attend the 31 May assembly in a published statement dated 28 May, printed here as Document 10. Committee chair Salim noted that there were UN resolutions not yet respected and that the C24 had not been consulted on the assembly, so it could not attend.

Under-Secretary Tang advised (successfully) that the Secretary-General not only stay away from Dili, but also avoid replying to the invitation. This, he said in Document 11, could block the PGET from its goal “to obtain some kind of recognition form the United Nations.”

UN reluctance to attend the 31 May assembly informed others’ reluctance. From a final invitation list of 21 countries (Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Philippines, Brazil, Germany, France, Britain, Italy, India, Iran, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, Switzerland, USA, USSR) and several arms of the UN, only six countries attended (India, Iran, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Thailand and New Zealand).

From London, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office informed counterparts that the United States and Australia were trying to avoid invitations that they might have to refuse to attend. Britain and the EEC were keeping a low profile, but would probably decline even if Australia attended. This is reported in Document 12, a Canadian diplomatic dispatch (other soundings found ambivalence in both Western and Asian capitals about whether to attend if invited).

In a memorandum to Australian foreign minister Andrew Peacock, reproduced from the official Australian document collection as Document 13, his Department of External Affairs weighed whether to attend. Australia’s decision, they thought, could sway the US, Japan, Canada and New Zealand. The DEA on balance recommended staying away, and Peacock agreed on the assumption that other Western powers would also do so, and wanted the decision delayed as long as possible.

Peacock finally declined the invitation on 30 May (Document 14), pointing out that he had wished to avoid an earlier decision that might influence others to stay away, and had thus been helpful to Indonesia.

Peacock made the decision, Australian officials informed their Canadian counterparts, even knowing that New Zealand and (reportedly) Japan had decided to be present – but it had been “on very fine balance up to the last minute” – as the Canadian mission in Canberra reported in Document 15.

The assembly duly met on 31 May and decided “with complete free will [and] without any form of coercion from outside” to petition for annexation by Indonesia, as the PGET telegrammed to Waldheim the same day (Document 16).

“We were in Dili a little less than 2 hours,” New Zealand diplomat Alison Stokes wrote in a report shared with New Zealand’s allies (Document 17). While 28 delegates unanimously agreed to seek annexation, she reported, there was no indication of how they had been selected and no option other than annexation on the table. Lest the outcome had been in any doubt, Stokes received printed information on her inward flight to Dili, stating that the Timorese had chosen integration into Indonesia. English-language signs to the same effect were on display as she was whisked back to the airport immediately after the ceremony.

The next step in the integration process would see Indonesia’s parliament send a five-hour mission to Dili to verify that the annexation petition was truly the will of the Timorese people. Indonesia again pressed the Secretary-General to attend this time (Document 18). Again, it was not successful.

New Zealand foreign minister Brian Talboys made a similar effort soon afterwards, trying to have Winspeare accompany this mission or visit Timor-Leste in June (Document 19, courtesy Maire Leadbetter). Despite support for his effort delivered verbally at the UN by delegates from Australia, Britain and the USA, the UN Secretariat was unmoved.

PGET and Indonesian efforts to host a UN presence shine though in a document package presented by the Indonesian mission to the UN in June 1976 (Document 20). In it, the PGET argues that the wish to integrate into Indonesia had been “kindling in the heart of each and every son of East Timor” for many years and calls on the UN to “to come to Dili and see for themselves how determined we are to be reunited with our [Indonesian] brothers.” Welcoming “the firm determination of the people of East Timor to re-integrate [sic],” Suharto also invoked kinship: “I do not feel as though I am greeting strangers today. I feel I am meeting my own brothers again, who were separated for a long time.” After a long recounting of Indonesia’s nationalist history that barely mentioned Timor-Leste, Suharto made it very clear that there would be little delay in “completing this process of integration.”

Meanwhile, Winspeare made his final report to the Secretary-General on his mission to see UN resolutions implemented – one that had not seen much success. In an eight-page letter to Waldheim (Document 21) he concentrated on the broad lines of his mission but also included the 31 May assembly in his discussion of self-determination. He reported that accepting any of the May or June invitations to visit Timor-Leste would not have been “appropriate” and that no UN Organs had been involved in any PGET “self-determination” steps.

For the Indonesian government, the story was closed. Officials in Jakarta could not look past the planned August 17 integration of Timor-Leste into Indonesia, New Zealand’s embassy reported in Document 22. When “that magic days comes, … all their troubles will be resolved by Timor’s disappearance as a separate entity,” the embassy reported them as feeling.

For its part, Fretilin promised again to fight on, saying it still controlled 80% of the territory. A statement by Mari Alkatari for the DRET (Document 23) again said that Indonesia had imposed the 31 May assembly to deceive, “an experience it acquired in 1969 at the time of the annexation of West Irian.” After the “puppet act of free choice,” Indonesia was replicating the tactics of other colonizers. Alkatiri condemned the countries that had lent their presence on 31 May, but praised the UN for its “coherent position” in support of true self-determination.

DRET again blasted the 31 May “ridiculous farce” in which “28 puppets” overseen by “armed guards” had not even been permitted to speak in substance with foreign observers. The statement, signed by Jose Ramos Horta and transmitted by the delegation of Mozambique to the UN (Document 24), rejected the “transparent charade” which concealed “a most horrifying drama” in Timor-Leste, and blasted Winspeare for merely parroting Indonesian propaganda.

Despite continued Indonesian efforts to draw a UN presence to Dili in July 1976, the UN avoided involvement, with the Secretariat’s department of political affairs and decolonization finding creative and polite ways to turn down invitations for the Secretary-General to visit Dili under Indonesian auspices (Document 25). The 31 May assembly had convinced no one in New York, and very few elsewhere. The 17 July Indonesian formal annexation of Timor-Leste would prove no more successful.

Compiled by David Webster.

Acronyms used:

C24 = United Nations Special Committee of 24 [on decolonization]

DRET = Democratic Republic of East Timor

EEC = European Economic Community (now the European Union)

Fretilin = Independent East Timor Revolutionary Front

PGET = “Provisional Government of East Timor”

UN = United Nations

To avoid online read errors, all diacritical marks have been omitted from names.